Late Thursday night, EU leaders accepted that their most ambitious funding idea for Ukraine would not survive. They had spent months debating an unprecedented proposal to turn frozen Russian central bank assets into a zero-interest reparations loan. The plan promised moral clarity and financial innovation, but it demanded legal certainty nobody could guarantee. Faced with unknown risks, leaders stepped back and chose a familiar path instead. They agreed to raise €90 billion through joint EU borrowing, leaving €210 billion in Russian assets untouched and immobilised. That decision quietly ended a project the European Commission once presented as transformative.

Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever stood at the centre of the opposition. He warned repeatedly that seizing Russian-linked assets would expose Europe to unpredictable legal and financial fallout. He argued that governments prefer certainty when risks escalate and consequences spread across borders. His position ultimately shaped the final outcome. The EU will now support Ukraine through common debt, abandoning the novel mechanism once promised to Kyiv.

From Ambitious Pitch to Growing Resistance

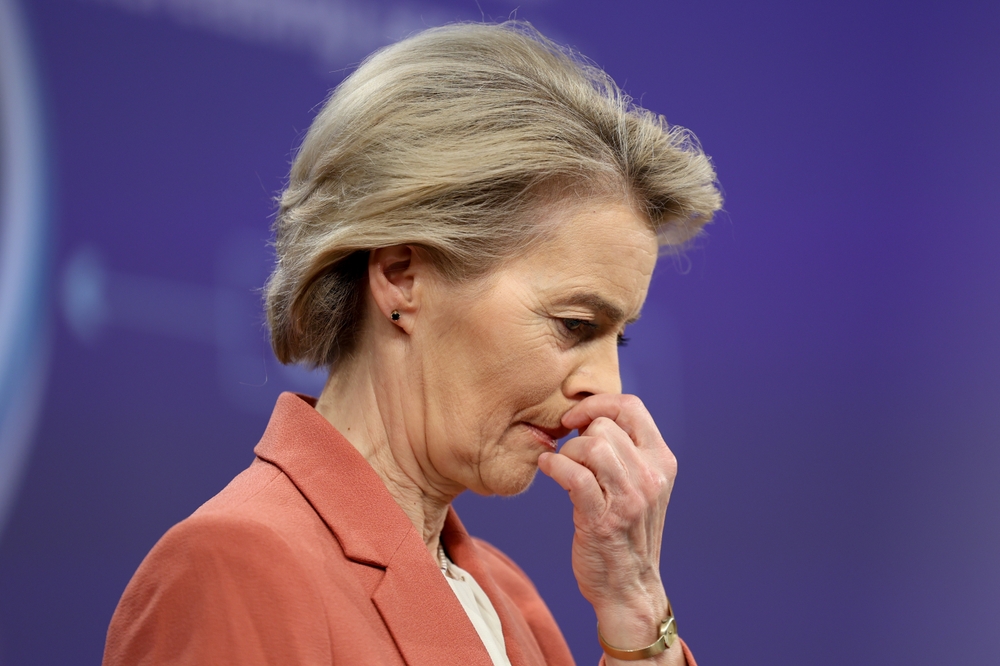

The idea first emerged on 10 September, when Commission President Ursula von der Leyen raised it during her State of the EU speech. She argued that Russia should pay for the war it launched, not European taxpayers alone. She proposed using profits from frozen Russian assets to back a reparations loan, but she offered no details. That lack of clarity soon became a problem.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz escalated the debate days later. He endorsed the proposal in a Financial Times opinion piece and framed it as both necessary and achievable. Many diplomats reacted with surprise, viewing the move as Germany setting the agenda for the entire bloc. The Commission then circulated a short, highly theoretical document outlining how the scheme might work. That document triggered strong reactions in Brussels.

Belgium responded sharply because it holds most frozen Russian assets through Euroclear. Officials felt excluded from early consultations despite carrying the greatest exposure. In October, De Wever publicly warned against spending Europe’s strongest leverage over Moscow. He argued that using the assets would eliminate future pressure on Russia. He demanded airtight legal certainty, shared risks, and collective responsibility across all asset-holding states.

An October summit failed to produce agreement. Leaders asked the Commission to explore several funding options instead. Von der Leyen nevertheless continued to frame the reparations loan as the preferred solution, suggesting leaders had agreed on the goal but not the method. That interpretation widened existing divisions.

Why the Project Ultimately Fell Apart

In November, von der Leyen presented three funding paths: voluntary national contributions, joint debt, and the reparations loan. She acknowledged that none offered an easy solution. Her letter addressed Belgian concerns directly, promising strong guarantees and international participation. It also warned of reputational damage and financial instability risks for the eurozone.

External events briefly revived support for the loan. US and Russian officials circulated a controversial peace proposal suggesting commercial use of frozen assets. European leaders rejected that approach and insisted Europe must control decisions within its jurisdiction. The reparations loan briefly regained momentum.

That momentum collapsed after De Wever sent a sharply worded letter to von der Leyen. He called the plan fundamentally flawed and warned it could undermine future peace efforts. In December, the Commission released full legal texts, but the European Central Bank refused liquidity support. Euroclear criticised the proposal as fragile and experimental, warning of investor flight.

Several northern and eastern states defended the loan publicly, citing Ukraine’s right to compensation. Senior Commission officials echoed that message. Still, doubts spread. Italy, Bulgaria, and Malta urged safer, more predictable financing options. Other leaders quietly agreed.

At the 18 December summit, leaders explored a final compromise involving unlimited guarantees. That language alarmed exhausted negotiators who suddenly faced vast potential liabilities. Fearing exposure tied to Belgian banks, leaders abandoned the reparations loan and chose joint debt.

De Wever later said he expected the outcome. He argued that no funding plan avoids real costs. He concluded that free money does not exist.